AI Garden Hose

In some part, this project was inspired by my previous effort to build a Terraform Provider for my sprinkler system. As that work was winding down I envisioned (with a merry twinkle in my eye) using that provider to power a booby trap that would activate my sprinkler system whenever an unwelcome guest got too close to the house.

But what if we could go even further? What if we could devise a means of both selectively choosing the target and delivering a concentrated blast of water to this hypothetical interloper?

Maybe, just maybe, I could accomplish this via (dramatic pause) ......AI??!?

The Plan

That was it. Once those charmed words had flickered across my consciousness, I'd crossed the proverbial Rubicon. My initial vision went something like this: I'd use one of the Raspberry Pi's I have lying around to give me the ability to remotely control a motorized valve attached to the end of my garden hose. Then, I'd connect a camera to the Pi to do live image capture. Finally, the crucial bit: I'd train an ML model to do object detection on that live feed, giving me the ability to automatically differeniate between friend and foe in real time, blasting the latter with a spray from the hose while letting the former proceed unbothered.

The Result

If you're interested in how I built it, read on!

The Hardware

I'll admit, I just kind of assumed that someone somewhere had already invented a garden hose valve that could be controlled via GPIO pins. It did take a bit of digging (and U.S. Solid seems to have a near monopoly on this), but in the end I wasn't disappointed as I found a GPIO actuated motorized ball valve that could connect to the end of a garden hose:

They had a few different varities but I ended up going with the 3 wire option so that I'd be able to turn it on and off without having to supply constant power. I was also intrigued by the fact that it could be powered by 9-24V AC/DC power. Full disclosure: AC power scares me. Power in general scares me. As someone who once planned to major in electrical engineering this admission is all the more humiliating. I could just never quite get the hang of Kerchoff's law, and as such, I have since lived in perpetual fear of touching a live wire. For that reason, I always try to use the absolute minimum amount of required power. In this case, a 9V battery didn't seem too intimidating and would theoretically fit the bill.

As nice as it would be, you unfortunately cannot just directly connect the GPIO pins to the valve input pins and call it a day. In order to power the motor in the valve, I knew I'd need another component beyond just a battery and a motor in order to implement the desired logic. What I needed was a way to control the current supply to the motor (the battery) via voltage (the GPIO pin output). Enter the MOSFET. If I speak too much about MOSFETs I'll quickly end up in over my depth but at a high level, they enable you to control the flow of electrical current from the source and drain terminals by changing the amount of voltage applied at the gate terminal. Awesome.

I bought a MOSFET online and with a bit of research came up with this diagram.

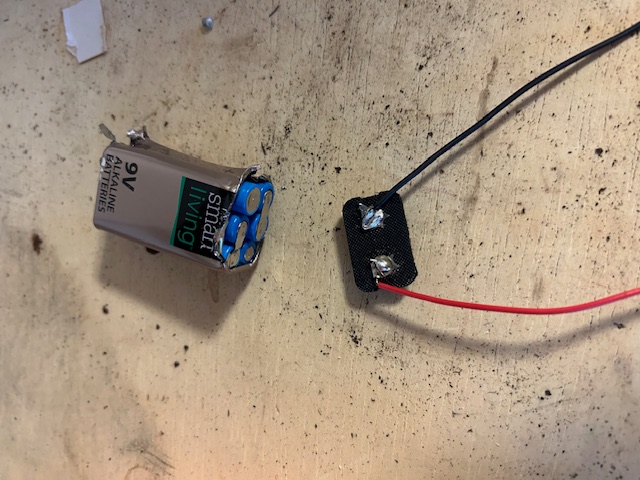

I set about wiring it all up but quickly realized that I'd forgotten to procure a connector for my 9V battery. Because I couldn't be bothered to spend $2 and wait a few days, I figured I'd try to make my own. Turns out that if you're willing to sacrifice another 9V battery you can rip the top off of it, solder on a +/- lead and you're good to go. Neat stuff.

I wired it all up, ran a simple GPIO pin output test and......nothing happend. Ugh. I reran the code a few times and I noticed that there was a very faint clicking sound coming from the motor. To test and see if my motor was working at all, I connected it directly to the battery and the valve turned just fine. After reading through various electronics forums, I noticed a common theme that seemed to fit my scenario: oftenimes the gate voltage needed for a MOSFET to functionally work is higher than the advertised value. For my particular model of MOSFET it seemed as though the common consensus was that I'd need at least 4.5V...which was a bummer because the RPi GPIO pin maxes out at 3.3V.

I found a few example circuits on these forums that would theoretically overcome this by means of stepping up the voltage (it would use the 9V battery as the gate voltage which could then be controlled by a second transistor with a lower gate voltage threshold and so forth). I tried a few of these circuits to no avail. I can't remember which forum I found it on but ultimately I decided to take the advice of a user who urged against "Rube Goldberg kluges" in favor of just buying a MOSFET with a gate threshold voltage that would actually work with 3.3V of input. Once it arrived I swapped it in and BOOM, it turned the valve on the very first time I ran the code.

The Model

The proliferation of ML related tools over the last few years has been impressive to watch. During my initial research I found at least 4 tools that all claimed to accomplish what I was hoping for. Under-the-hood the process for each was more or less the same: you take a bunch of pictures of the thing you want to identify in various settings and from various angles. Then you manually label the "thing" you're hoping to detect. Finally, you pass it through their machine learning algorithm so that it can calibrate the series of weights it uses to build the model that makes a determination as to whether or not the "thing" is in the image or not. This is a gross oversimplification but to go into the weeds of object detection (and machine learning more generally) would take far more time than I have at the present moment.

For the object in question I chose...myself. This may seem like a foolhardy thing to do but I found it difficult to convince anyone else to be the test subject for a project that would result in them getting drenched.

For the specific ML tool, I ended up choosing Edge Impulse given that it had built-in compatibility with the Raspberry Pi 4. What was really cool is that once I installed the client library on my Pi, it allowed me to do live image capture directly from the device. As a funny aside, it required a button click to take the picture which was a challenge since I wanted to be in the frame but I also needed a lot of pictures. In order to take several pictures in a row, I pasted this javascript snippet into the console on the page so that it would automatically, programatically "press the button" every 15 seconds.

setInterval(function() {

document.getElementById("input-start-sampling").click();

}, 15000);

Once my camera was snapping away every 15 seconds, I basically just milled about in front of it for several minutes in order to get enough content to train the model. I'm sure it looked pretty ridiculous. At one point I even dragged my trashcan into the frame to provide some variety to the model and to make extra sure so that it knew that I am not a trashcan. Ultimately I collected about 50 pictures, labeled them, and then built the model from that.

Edge Impulse allows you to do live classification, which was really cool to see the model at work in real time:

Yes the image is upside down (because of the way the Pi Camera hangs in my setup) but an upside down Caleb will actuate a motorized ball valve just as well as a right side up one.

I do want to take a second to marvel that the model could reliably detect my presence with such a small sample size (~50 images). Now there is a relatively major caveat in that this model is hyperspecific: the frame of the camera doesn't move, I'm wearing the exact same clothes. and there's limited change in the background scenery. If any of those things were to substantively change I would expect marked degradation in the model's performance. Still super cool though.

Every time I showed this off too, I'd lamely feign that the software had come up with that label on it's own.

The Software

The actual code required to power this was a relatively small lift given how much boilerplate code Edge Impulse gives you out of the gate. I ended up having to stitch together a few different modules as one of their camera modules was no longer compatible with the RPi camera, but even still it was a minor change. Ultimately I went with a simple implementation that would trigger an interrupt function that turns on the hose whenever the presence of the object was detected with >90% confidence and lets it run for a few seconds before turning the hose off again.

The Setup

Pretty high tech, huh?:

Takeaways

Utimately what I found really compelling about this project is that the three major components (the hardware, the software, and the model) are more or less modular, making the possible applications nearly limitless. For example, I could change the model to detect the various wildlife that routinely decimates my front shrubbery. I could change the hardware to be a smartlock than unlocks when it sees my face. I could change the software to also send me a text message alerting me to the presence of an intruder. You get the idea. Imagine an infrared camera and microphone that alerts parents when an infant sleeping in a crib either spikes a high fever or an irregular cough, speeding up the time-to-intervention and potentially saving lives: still the same three basic components.

It's also worth noting that the barrier of entry for a project like this has come down significantly in the recent past. I've had a kernel of this idea for quite some time, but the amount of time and effort always seemed insurmountable. With the rise of ML-as-a-service platforms, AI code assistants, and GenAI chatbots, that which would have taken specialized knowledge and a great degree of time even 5 years ago can now be prototyped fairly rapidly with a modest degree of know-how.

However, that "disruption" in ease of access doesn't feel symmetric though. The hardware/electrical engineering resources available seem to really lag compared to the software. This definitely feels like a sector that is ripe for "education disruption", particularly if/when robotics has its moment this generation.

Finally, probably most importantly, be careful what images you share of yourself online because your enemies (or friends) may use them to train ML models to spray you with their garden hoses.