Writing a Terraform Provider For My Sprinkler System

This past spring, I had an Orbit Bhyve Outdoor system timer added to my home's sprinkler system. I've never owned an irrigation system before and now that it's operational I've been having wayyyyy too much fun playing around with the different settings. The timer comes with a relatively straightforward mobile app and web interface that lets you do things like set schedules and run ad hoc sprinkler sessions.

Most folks would probably just set a schedule and let it do its thing, but as I was tinkering with my lawn a few weeks ago, it got me thinking: could I use Terraform to control my sprinkler system? After all - why do things the easy way when you can spend hours building redundant automation? Shouldn't we use Terraform to terraform? Why rely on rain clouds when you can rely on THE Cloud? Ok, I'll stop. Had to get that out of my system.

All jokes aside, I'm always looking for ways to expand the breadth and depth of my understanding of the tech I use on a daily basis and I'm also a firm believer that you learn best when you're having fun. This project seemed like a great opportunity to do both.

Initial Exploration and Fundamentals

Before I set about starting, I wanted to make sure that some fundamental components were in place for this to be a feasible project:

-

That a Terraform Provider didn't already exist. While this wasn't a hard and fast requirement, it definitely takes the wind out of your sails a bit to know you're reinventing the wheel. Turns out that there was not one, which wasn't terribly surprising given that it is a somewhat obscure piece of yard tech.

-

API Access and documentation. As I was doing my research, I quickly came to the conclusion that the Orbit API is not officially documented. However, there are a couple of very clever people out there who have set about reverse engineering some of the important API calls and have used it to build their own clients. I found this JS implementation by Brian Armstrong to be immensely helpful in building my own client.

So far so good! Before we go any further, it's important to lay a bit of the ideological groundwork for what a Terraform provider is and how you interact with it. Terraform, at its core, is essentially a finite state machine: you track state and change that state based on a series of inputs and outputs. In order to perform that state change, you need a way to interact with the end resources themselves (in our case, a sprinkler system). This is where your API client comes into play. The first step in writing a Terraform provider is writing an API client that integrates well with the CRUD operations and reconciliations that the Terraform provider will eventually mediate. A well written client makes the Terraform provider implementation far more seamless. That's a sentiment that's widely shared across the community and I've heard it distilled down to the following: shove all your API weirdness into the internals of the client.

Writing an API Client

Terraform providers (and their associated clients) are written almost exclusively in Golang, so the first step in this project was to convert the JS implementation mentioned above to Go. A few notes on this process:

-

I pretty quickly discovered that the Orbit API uses WebSockets. This seemed like a rather strange design choice given the system. The interaction consists almost entirely of client-initiated requests followed by replies from the server (Me: "Turn on zone 3 for 5 minutes!", Sprinkler System "OK!"). It's also a front yard sprinkler system...not the kind of tech that should require persistent, bidirectional communication. I'm still not sure why they didn't just use a REST API. Oh well. I tried to obscure the WS implementation as much as possible by making it into its own package that was then invoked by the client package to make the interface as clean as possible.

-

ChatGPT was a HUGE help in doing the code port. I just pointed it at the source repo and said "convert this to Golang" and it got it >90% correct on the first try. Everyone's got their "take" on LLMs so I won't bother going into detail on mine, but for routine, somewhat mundane tasks like this, it saved me hours of work. Sure, it hallucinated a couple of functions and libraries but those are pretty easy to weed out. It's a great feeling getting to work on the stuff that most interests you while leaving the drudgery to automation.

It's been a while since I've written anything substantive in Go, so I was a little rusty on some of the syntax. For the scope of this project I was mainly interested in one action: turning on a sprinkler. Under the hood, the API call for this action is pretty straightforward - you just need to pass it a ZoneID and the number of minutes you want it to run, along with some static values. I called this function StartZone. We'll see in a second, but the API client ideally supports CRUD operations. The "create" and "update" in my case are the same function: StartZone (calling StartZone on a running zone just updates the time to the new value).

func (c *Client) StartZone(zoneId, minutes int) error {

conn, err := c.ws.Connect(c.token, c.config.DeviceId)

if err != nil {

return err

}

return conn.WriteJSON(map[string]interface{}{

"event": "change_mode",

"mode": "manual",

"device_id": c.config.DeviceId,

"timestamp": time.Now().Format(time.RFC3339),

"stations": []map[string]interface{}{

{"station": zoneId, "run_time": minutes},

},

})

}

There was also a StopZone functions (which turns off all sprinklers), which was a nice candidate for the "delete" operation. The "read" call was a bit tricky because there wasn't really an equivalent operation available against the API that I could find. I ended up just stubbing out a GetZone function that returns a static value.

Finally, I wanted to test it locally prior to using it in the provider. Since I was using my personal Orbit login creds I wanted to be careful not to commit them back to the repo (which would be very embarrassing and would also give anyone the ability to turn on my sprinklers). I used the Viper library to setup a config.yml and with just a few lines and an appropriately scoped .gitignore I was able to extract the login config on every run without exposing my credentials.

Once I had all that in place I figured it was time to give it a test. I ran go run main.go, sprinted to the front of the house and, lo and behold, the front flower bed sprinklers were going full blast. Awesome.

Writing the Provider

I won't lie, the idea of starting from a blank slate with my provider was a little intimidating. Thankfully, Hashicorp has an excellent example repo and series of tutorials where they build a mock provider. For the sake of brevity I'll stick to high level concepts I took away after setting up my provider.

My primary goal was to implement a single resource,bhyve_zone, that would accept a ZoneID and a number of minutes as the input.

Schema is important. Schemas are defined for the root provider itself, along with Data and Resources as well. If you don't have a solid idea as to how your data needs to be structured and the format in which it is expected then you need to take a step back and re-evaluate all the different configuration possibilities. In my case this was pretty simple: for the provider it was just the login information and for the bhyve_zone resource it was a ZoneID and a number of Minutes. For the resource I also figured I'd play around with the Terraform concept of 'Computed' attributes - these are values that can not be directly manipulated by the user. I used the example attribute from the tutorial library: last_updated, in case I wanted to know when a particular sprinkler last ran. Here's an example from my code:

resp.Schema = schema.Schema{

Attributes: map[string]schema.Attribute{

"id": schema.StringAttribute{

Required: true,

},

"last_updated": schema.StringAttribute{

Computed: true,

},

"minutes": schema.StringAttribute{

Required: true,

},

},

}

Keep track of your Configure functions. It took me some trial and error before it clicked that the Configure function is how the Data and Resource objects access the API client defined in the provider.go. When I ran my first terraform apply I actually got a successful output....except my sprinklers didn't turn on. After digging into the code I realized that while I defined a new client, I had never actually initialized it in the provider.go. Doh!

Think carefully about how you want the state to change. This was probably the biggest revelation to me when I saw how it works under the hood. I'm not entirely sure what I thought was happening within a provider previously, but I think I assumed that the API client responses shouldered a larger share of the state updates. Assuming your API client is sensibly configured, by far the most challenging part of defining your CRUD functions is figuring out exactly how the state needs to change based on the input and the action, and then making sure that is reflected back into the state. Like you would with a finite state machine, I would suggest drawing out a diagram and what the expected state would be at each stage. Bear in mind that state can change outside of a Terraform, so these runs are also about forcing the resources back into alignment with the statefile.

In the end, once I had it aliased to point at my local built provider, I put together a very rudimentary example called resource.tf:

terraform {

required_providers {

bhyve = {

source = "github.com/gillcaleb/bhyve"

}

}

}

provider "bhyve" {}

resource "bhyve_zone" "zone" {

id = 5

minutes = 5

}

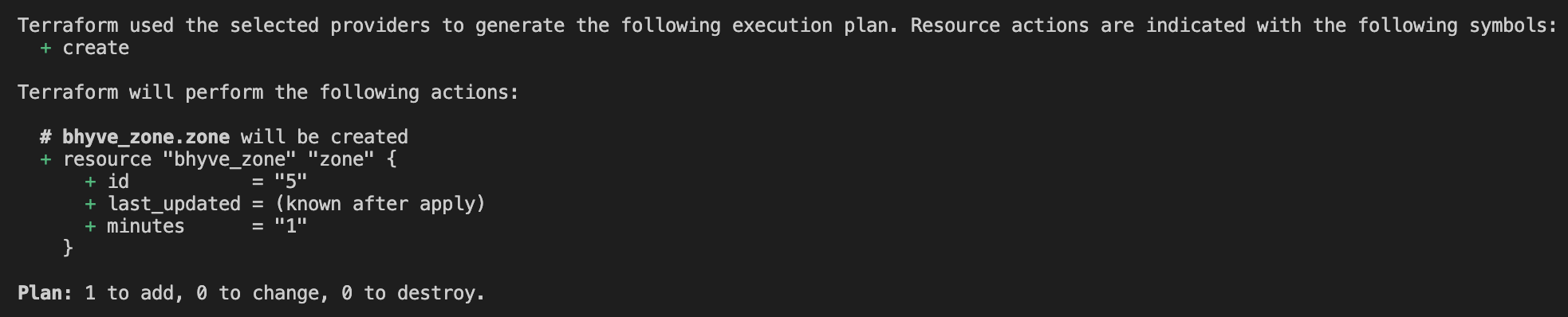

When I ran terraform apply against this, I got the following output from the CLI:

Once again I sprinted to the front of my house just in time to see the sprinklers spring into action.

Success!!

Closing Thoughts

I'll fully acknowledge that most aspects of this project were rather contrived. First, the app already had a very functional client for accomplishing the desired operations. Next, the very premise of running your sprinkler system with Terraform is probably something that only appeals to a tiny subset of software professionals, so the number of people who would conceivably ever use this is extremely low. Probably only me. Finally, the resource itself that I implemented doesn't make a ton of sense in Terraform for the simple reason that it is more or less stateless. When you run a sprinkler zone, it runs for a few minutes and never again unless you manually run it...so tracking the state is largely pointless. It would have been a bit more prudent to implement some of the watering-schedule features in the provider, but I didn't because it's far more rewarding to see your sprinklers instantaneously pop up out of the ground at the click of a button than it is to have a schedule run 12 hours later.

If you want to check out the code for this project you can find the Orbit Bhyve Go API Client here and the Terraform Provider here. I'll add the obligatory disclaimer that both of these repos are purely prototypes and in no way complete or production ready - there's lots of unused boilerplate/template code still in there and I don't think I wrote a single test the entire time.

All that being said, I had a blast with this project. I use Terraform on a regular basis in my professional capacity, so getting to do a soup-to-nuts implementation was extremely informative and my hope is that it better equips me to contribute to "real" Terraform providers in the future. Thanks for reading this far -- I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did. 'til next time!